Ed Pulaski wiped sweat from his brow as he squinted through the heavy smoke. He caught glimpses of the inferno beyond, threatening to hem them in. Whirling fire raged up like small tornadoes amongst the burning trees. Mature pines snapped off like twigs in the vacuum of the flames. Everything wasburning, flora, fauna, even the rocks. It was as if the world were ending. Wallace, he knew, will have burned to the ground by the time he got out. If he ever survived this.

Behind him his crew chopped and shoveled, hollered orders to one another as they tried desperately to create a barrier between them and the oncoming fire. The roar of flames was almost deafening. His throat hurt from the yelling and the heat. Ed knew it was hopeless. It was just too dry. The fire season had started too early, and there was just no stopping this. Several men had already perished in the flames — worse flames than his crew were currently fighting, but they were coming. Ed needed to get these men out, and he needed to do it now.

–––––

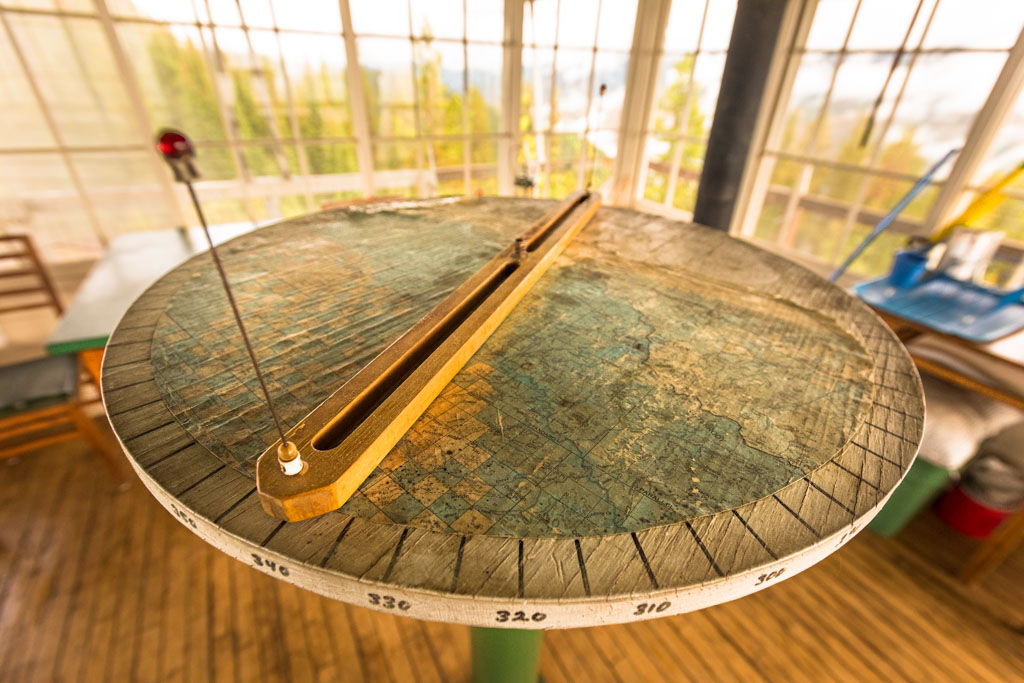

The Arid Peak Lookout in the Idaho Panhandle National Forest was built in 1934 to help spot wildfires that may have been sparked by the Milwaukee Railroad Line. In 1969 its doors were closed and remained so for more than 25 years before its renovation. The lookout was fully restored in 1997 and is available for rent to the public. With its 360 degree view of the Bitterroot Mountains, it can be found on the list of the National Register of Historic Lookouts.

Sept. 22 was the last possible day for us to stay overnight at the Arid Peak Lookout. We were hoping for ideal photo conditions. The weather report said we’d get a break in the clouds in the late afternoon. What we got was thicker, greyer, rainier clouds. You might say we got skunked. But in North Idaho, that’s never all you get.

Before we were married, I told my wife, “There’s one thing you should know about me. I don’t camp in the rain.” As I drove east on I-90 toward Wallace, Idaho, it was raining, and I wasn’t very happy about it. However, Joel Riner and I had made plans to meet outside Avery, and I wasn’t about to call him up to say I wasn’t coming. I might be a little late, but I would be there rain or shine. Besides, I’d never been over Moon Pass and my adventurous side was eager to see what I’d been missing.

If you live in the Pacific Northwest you’ve heard tales of the Great Fires of 1910. There had been a drought that year and sparks from the Milwaukee Railroad Line had quickly become a serious problem. By mid-August it was estimated there were up to 3,000 wildfires burning between Washington, Idaho, Montana, and even British Columbia. Then, on Aug. 20, the region was blasted by gale force winds that whipped thealready out-of-control fires into an outright firestorm that killed 87 people (most of them firefighters), burned three million acres, darkened the skies as far east as Boston and as far south as Denver. Boat captains as far out on the Pacific Ocean as 500 miles were said to have complained it was impossible to navigate by the stars due to a sky filled with smoke. Several towns in the Silver Valley, including Wallace, were burned to ash. It’s little wonder the fire is often referred to as the Devil’s Broom; Hell had set upon North Idaho.

Story continues after a quick message from our sponsor below.

As I passed through the Silver Valley the only signs of the Great Fires are the apparent sparseness of timber on the surrounding hillsides. Much has grown back in the hundred-plus years. Drive through Wallace today, and you’d never know it had ever burned. Visit their museums and you’ll see the devastation.

–––––

His mind made up, Pulaski hollered to his crew and they came running, all 45 men passing along the message from one man to the next. He looked each man in the eye, lines of sweat streaking their soot blackened faces.Their expressions a mix of determination and fear.

“These fires are going to cut us off,” he said. “The way I see it, we’ve got one chance.”

The men nodded their agreement, and leaned in eager to hear his plan. Hope added to their expressions.

“We head for the old mine shaft down on Placer Creek,” he said. “We could make it, but we’ve got to move now. If we stay here, we’ll never make it out.”

The journey down the mountain was a race through Hell, fiery demons rushing at their backs. When they finally reached the old mine shaft, it appeared as a dark, damp hole in the mountainside, more a tomb than a sanctuary. But they practically dove in, preferring to welcome what perils might lie ahead than to face the devil flames roaring behind them. Ed leaned against the tunnel wall to catch his breath and wondered if he’d made the right decision. Now that they were here there truly was nowhere else to go. No way out.

–––––

After some miles on rough roads — we were glad I’d brought the Jeep — Joel and I reached the Arid Peak trailhead. The rain had slowed to a sporadic sprinkling, but the sky was still quite grey. Possibly more grey.

We checked our gear, I tied on a load of firewood and we started the three mile trek to our new home. It was slow going, and, with the extra weight from the firewood, my hips and legs quickly cramped and fatigued, making the going even slower.

“You need to stop?” Joel asked.

“I’ll warm into it,” I said. I was happy a mile or so later when I discovered this to be true.

We enjoyed the early fall colors in the undergrowth and groundcover. Brilliant reds and golds seemed to edge everything up to waist height. It was a beautiful contrast against the backdrop of silver trunks, evergreen needles and misty rain clouds the color of lead.

It was a quiet journey, all wildlife seemingly having tucked away for the weekend to wait out the weather. But Joel and I kept up a conversation to pass the time. Then, Joel stopped and lifted his camera. It took me a few steps to realize he was no longer moving forward, and I came to a sudden halt. We were in the middle of a misty grove of nearly identical trees, their trunks having been oddly affected by some natural phenomena. Not far from the ground, each silver trunk jutted suddenly Northward into an arcing bend before returning to its upright growing position. It was a shape that resembled the left half of an ace of spades. Joel took some shots, and we moved on. I wondered if it had been caused by wind, or perhaps by fire.

–––––

Pulaski and several of the other men fought against the flames at the mouth of the tunnel. Wet blankets, shovels and dirt, their only weapons against an adversary, near godlike in its power to destroy. But he’d not come this far to die, and so he pushed on despite fatigue. Despite his aching head and muscles. How much longer could these fi res burn at the entrance? They just needed to hold them back. Ed was so tired, his breathing ragged and lacking oxygen. Without warning the man beside him swoons and crumples, loses consciousness. Ed thought to call for help. But then, his own vision blurred a moment. He staggered, trying desperately to keep his feet. Then, all the fires seemed to go out at once, and he was falling through utter darkness wondering if he’d died or if he’d ever hit the ground.

–––––

The tower is wonderful. It wasn’t like camping in the rain at all. In fact, to my pleasure, it wasn’t much like camping. It was more like crashing at a friend’s house…in a tower, on top of a mountain, with no power, and nothing but a wood stove for heat.

That night the clouds thickened and we were left in complete darkness. If we looked hard enough, we could see the lights of Wallace reflected faintly off the clouds to the north. We hoped for a break in the clouds come morning. We ate our meager no-cook dinners and shared stories in the dark for as long as possible before the cold set in. Then, finally, Joel opened the wood stove and started the fire.

–––––

Shaking his head didn’t change the roaring in his ears. Pulaski opened his eyes to find himself lying on the tunnel floor away from the entrance. Beside him were a few others. They all seemed to be unconscious, but breathing, though he couldn’t be sure in the flickering dimness. Outside, the fires still raged, though it seemed they were safe here for the moment.

It was difficult to judge the time. He estimated it must be nearly midnight. The men were exhausted. A few had even died. Ed didn’t want to lose any more men. They’d stay here and wait it out. It couldn’t last much longer. There couldn’t be much more left to burn. He wondered what the world would look like once the fire had passed. There would be nothing left. A world of blackened trunks and grey ash.

One man, apparently seeing a gap in the blaze, jumped to his feet and announced, “I’m getting out of here.”

Pulaski got to his feet as the man approached the entrance to the mine. Five men dead. Five too many. Anyone who tried to escape now would never survive, and he wasn’t about to lose another man. Not one more man.

Looking around, he could see others considering the option. If this man left the tunnel with apparent success, others would follow. Ed couldn’t let that happen. There would be nothing he could do to keep them there.

As the man made ready to exit, Pulaski drew his pistol and took aim. “I will shoot the first man who tries to leave this tunnel,” he shouted.

The man froze, considering Pulaski’s determination. Then, slumped to the ground to lean against the shaft wall, his own determination extinguished. The other men were content to wait as suggested.

Ed Pulaski and his crew fought the Devil’s Broom for two days. Then, on Aug. 22, the sky just broke open and it began to rain. Ed Pulaski would go down in history for saving the lives of 40 of his 45 man crew, and The Pulaski Tunnel Trail and mine would be officially listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

–––––

The morning brought clouds so low and so thick it felt like we were in some other world. The grey swirled asit moved past us, yet it never seemed to go anywhere. It just kept coming, like an airplane trapped in a never ending cloudbank. After a few more hours we caught a quick break. Joel wasted no time, grabbed his camera and got to work as I wrote a quick entry in the journal we found on the bookcase. I seem to recall writing something about clouds and getting skunked by the weather.

On our way back down the trail, I learned the difference between Bruce Springsteen and Bruce Willis—it was an honest case of mistaken identity. And when I finally made the descent back into Wallace, I pulled off at a little sign that read, Pulaski Tunnel Trail and learned a little something more. One thing being that there are far too many opportunities, too much history, too much beauty to every truly get skunked when you’re on an Idaho adventure.

By Toby Reynolds

Photography By Joel Riner